By Savannah Latimer, Howard University '23, Health Career Connection Alumna

January 2023

Philadelphia, Can You Feel the Love?

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is the “City of Brotherly Love,” but some areas haven’t felt “loved” for a while. Beyond the impact OF COVID-19 on the city, the smaller, northern neighborhoods have been increasingly neglected for the past 10 to 15 years, thanks to racial segregation and disinvestment. Most of Philadelphia’s northern regions of neighborhoods are separated by race, with white residents in extremely low numbers or nonexistent. The lack of white residents racially deterred investments in those poorer neighborhoods, causing a lack of healthy food and an increase in poor health rankings and outcomes.

|

Growing up, I spent many weekends at my grandmother’s house in Feltonville, North Philadelphia. As the years progressed, I witnessed a steady decline in the neighborhood's appearance, safety, and overall quality of life. I went from playing on the sidewalks with my cousins to rushing into my grandmother’s house and locking the doors. My cousins and I went from walking to the “Papi” store to get a quick snack to barely buying anything from the store because almost all of the inventory was unhealthy. As a family, we have seen the neglect of my grandmother’s neighborhood reflected in her life.

|

|

The lack of healthy food options became very apparent when my grandmother couldn't find affordable fruits and vegetables within a four-mile radius of her home. My mom and her sisters resorted to buying produce in their suburban neighborhoods to bring to my grandmother. For many Americans, a healthy diet is out of reach - the result of generations of disinvestment and neglect in urban neighborhoods, as well as the challenge of sustaining or attracting businesses to certain areas with distribution challenges. Families, like those in Feltonville, are missing out on affordable access to nutritious food and the economic opportunities, like jobs and revitalization, brought by healthy food access.

So, when I was given the opportunity to conduct a pilot study based in my hometown of Philadelphia, I knew I wanted to focus on the food insecurity crisis in my grandmother’s neighborhood. The pilot study, Living in a Food Desert, focuses on my grandmother's Feltonville, North Philadelphia area. In Feltonville, the poverty rate is double the national average, and the lack of healthy and affordable food options leads to quick and cheap food solutions. The fastest and most inexpensive food options are at the local “Papi” stores, where you can buy anything from dollar chips to cheese steak platters for under ten dollars.

Living in a Food Desert was conducted to support the research hypothesis that Philadelphia’s most neglected neighborhoods are experiencing serious food insecurities due to years of racial segregation and disinvestment. A cohort study was conducted through a survey to obtain the necessary data to support the hypothesis. Testimonials and conversations were obtained to convey the true emotions and challenge the residents of Feltonville face, and helped to understand the magnitude and hardships of food insecurity in the community. Eighty-six Philadelphians ranging from 18 to 79 years of age in the Feltonville area were surveyed regarding their overall health and the impact that living in a food desert has on their lives.

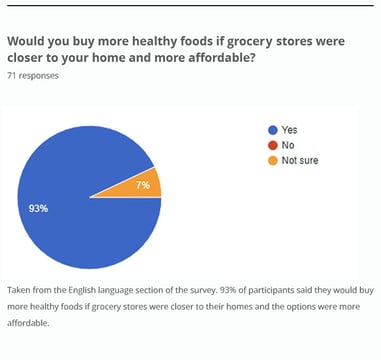

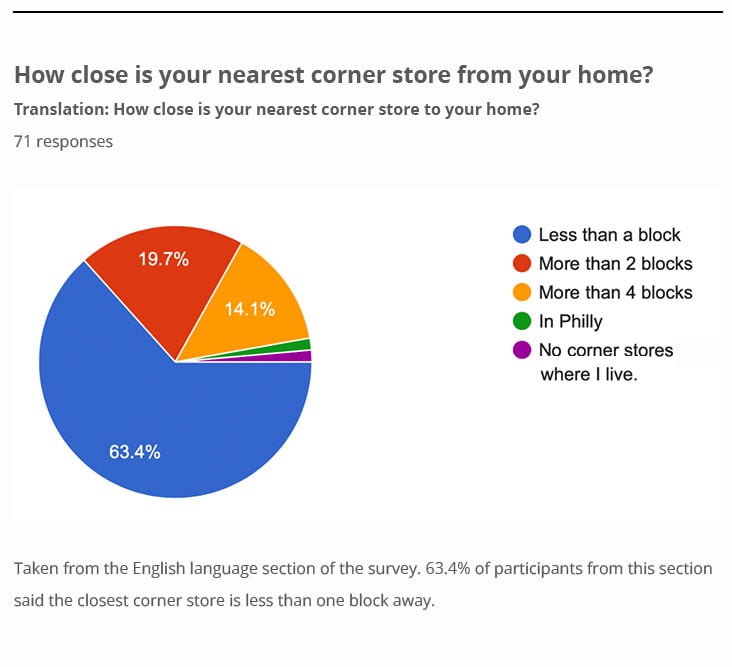

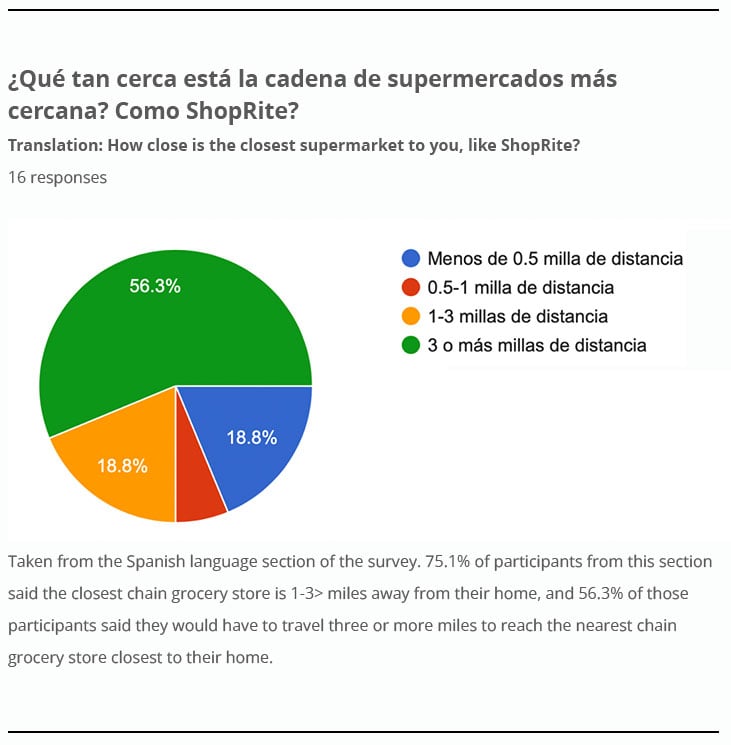

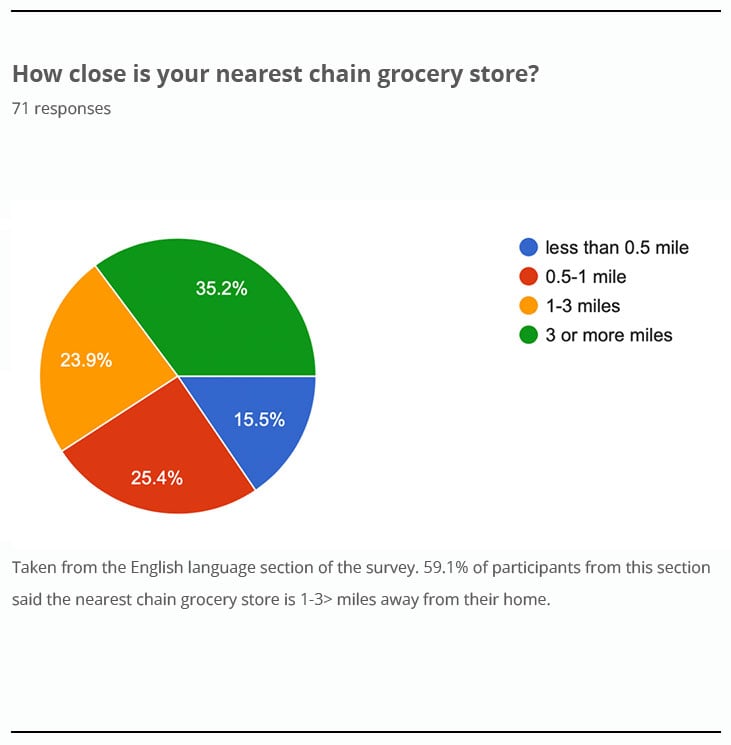

The survey was provided in English and Spanish to allow for inclusivity, as 64% of Feltonville’s population is Hispanic, and most are Spanish-speaking only. 92% of participants said they would buy healthier foods if the grocery stores were closer and more affordable. 86 participants said they would spend $50-$150> more weekly to buy healthier options. 60% of participants said they only eat 1-2 servings of fruits and vegetables daily because of the low availability. Lastly, 29% of participants said they have high blood pressure, and 43% said their current weight is a health concern, all due to their eating habits.

In conclusion, this study of Feltonville residents residing in an area of the city where healthy food solutions are scarce and expensive adds confirmatory data showing that these residents need more affordable healthy options to be closer to their homes. With the average income in Philadelphia being less than $50,000, coupled with the lack of citywide official support, these residents are not afforded the same advantages as their suburban counterparts.

Mytonomy intern Savannah Latimer visits the Philadelphia neighborhood she spent time in as a kid to learn about food inequality - and what makes a “food desert.”

“Corner Stores are not the enemy. They are small businesses trying to provide a service to the community and the owners are trying to make a living.

At the same time, they can be part of the solution. They have to make it affordable to have fruits, vegetables and fresh foods available.

That's my hope.”

— Father Charles Ravert, St. Ambrose Church, a Roman Catholic Parish in North Philadelphia founded in 1923

So, why don’t Philadelphians just eat healthier?

- Most Philadelphians surveyed in the Feltonville area said healthier food options would improve their overall health, proximity and affordability deter them from obtaining healthy food. Most are low-income earners and have to strategically manage their money down to the penny to get to their next paycheck. Healthier food is not only more expensive, it is often inaccessible in their neighborhoods. Healthier foods cost residents more in both time and money than the grocery items they are familiar with and are able to budget for.

- The average median income in Philadelphia is $49,127, ¾ of the national average

- Between the months of January 2021 and December 2021 the average rent for the greater Philadelphia area increased from $1604 to $1755 a month.

- Philadelphia’s poverty rate is 23.1%, which is double the U.S. average.

- Many people in study reported sharing their vehicles with other people in their households. With one vehicle split among several adults, the demands of work and daily necessities leaves minimal time to drive to an affordable source of healthier food - one that may even be outside the city.

“Today you see more children growing up on quick things...things that they can grab or order.”— Marisol Latimer, Feltonville native

Why is living in a food desert a problem, and what are the other significant impacts in Philadelphia?

|

|

| 21% of Philadelphians rated their health as poor or fair in 2020. |

1 in 3 adults struggled with obesity, while a little over 1 in 5 children ages 5-18 in public schools lived with obesity in 2020. |

|

|

| Most people have to travel over a mile to their nearest grocery store, where they would have to spend $50-$150 or more weekly to eat healthier. This is effectively impossible for low-income residents living paycheck to paycheck. |

Many of the neighborhood's population over 40 struggle with high blood pressure, hypertension, and diabetes related to their eating habits. These ailments may be exacerbated by other factors like lack of exercise, smoking and/or family history. |

There are ways to help the residents of Feltonville. First, a community-education effort to inform residents about how to make small but impactful shifts in their eating habits to improve their overall health. This could be accomplished through a series of "healthy food habit" workshops at the local Roman Catholic church, St. Ambrose Parish, led by Father Charles Ravert, and where many Feltonville residents already gather regularly. Father Charles would be accompanied by a local dietitian to provide the community with the most accurate dietary information. Second, bring awareness to the issues seen within the community. Healthy People revealed that their initiative of informing the public through leading health indicators in their health reports has improved the nation’s knowledge of these indicators and helped improve these indicators by 34.6% in some areas. Shedding light on the lack of healthy and affordable food solutions in Philadelphia’s residential areas coupled with the low-income rate in the city gives people the motivation to demand help from city and state officials who can allocate the necessary resources and funding to better the food insecurity issues at hand.

“... The city has to get involved… and have more responsibility… or nothing’s ever going to change.”

— Elsie Mañon, a Feltonville resident for over 20 years

How Health Systems & Plans Can Use Mytonomy's Content to Start a Conversation

Food insecurity is not a new issue in the United States. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. fought to bring healthy food to low-income citizens, famously asking: "Why should there be hunger and deprivation in any land, in any city, at any table..."

Access to healthy food is one piece to the solution of this issue. Education is the other. Mytonomy can play a key role with its expansive catalog of healthy eating videos. From healthy alternative recipes to portion control and plate planning guides.

Mytonomy's content can help providers and health plans to start conversations about food insecurity.

Other videos include:

-

- Shopping Smart at the Supermarket

- Vegetarian Minestrone Soup

- Reading Food Labels

- Food Choices

- Create a Food Schedule

- Food Choices and Portions

- With these video education modules, anyone can gain the knowledge to make better-informed choices regarding their food consumption and learn to create healthier everyday meals.

- Mytonomy’s commitment to diversity through inclusion is at the forefront of all our content creation. In this spirit, Mytonomy provides culture-focused food videos offered in English and Spanish:

- Eating Traditional Puerto Rican Food (Eating Traditional Puerto Rican Food)

- Managing Your Diabetes While Eating Soul Food/Southern Comfort Food (Managing Your Diabetes While Eating Traditional Southern Comfort Food)

- Patients learn how to still indulge in their cultural and comfort foods while still making healthy choices that will lead to better health, in the long run

- Mytonomy is also looking to implement a Food Insecurity module to help better patients who live in food deserts or experience food insecurity for other reasons, better their health according to their particular circumstances.

Access to healthy and affordable food options is necessary. No one should be forced to make unhealthy choices for themselves or their family because of geography, demographics or economics. The knowledge of what is and is not a healthy food choice should be easily available to all. Meaningful and quick solutions are imperative for those experiencing food insecurity and living in a food desert.

Mytonomy’s healthy food videos help increase patient knowledge surrounding food, decrease stigmas and shame regarding saying “no” to unhealthy options and encourage healthy changes in one’s diet.

Disclosure statement: This pilot study was funded by Mytonomy, Inc. as part of a summer internship through the Health Career Connections (HCC) Summer 2022 Mid-Atlantic Cohort. Pilot study participants were provided with a gift certificate and a water bottle valuing $16.54. Special thanks to The Archdiocese of Philadelphia, St. Ambrose Church, Father Charles Ravert, Elsie Mañon, and Marisol Latimer.